The term "donju"—referenced by media and academia as a key symbol of North Korea's marketization—refers to the nouveau riche who emerged after the "Arduous March" famine. As children and driving forces of North Korea's marketization, they built their wealth alongside the growth of the market economy.

Starting primarily in distribution, the donju's influence gradually expanded across neglected sectors of the economy and industry—mining, fishing, transportation, and real estate.

Wherever the donju turned their attention, new services and employment opportunities emerged, distribution networks flourished, and the grim faces of people cut off from state rations brightened once again.

However, after 2020, the donju rapidly collapsed. The primary cause was the Kim Jong-un regime's establishment of a "New Economic Order." Using COVID-19 as justification, North Korea implemented unprecedented anti-market policies that shrank markets, restricted individual economic activity, and brought down most donju in the process.

But that wasn't the end of the story. Recently, new forces have been rising under Kim Jong-un's "New Economic Order." We call them the New Donju class.

This series examines the rise and fall of the donju under the Kim Jong-un regime. (JEON Song-jun/KANG Ji-won)

◆ What Did the Donju Do?

Let’s illustrate the role of the donju—the protagonists of North Korea's marketization—with a concrete example.

In the late 2000s, when the Korean Wave was at its peak in North Korea, South Korean products were in such high demand they "couldn't be sold fast enough."

What's remarkable is that shortly after a new movie premiered in South Korea, people could be seen walking the streets of North Korea wearing identical outfits to those worn by the film's protagonists. How was this possible?

A smuggler in Sinuiju, North Pyongan Province, would import memory cards containing the film footage into North Korea via China, timed with the movie's release in South Korea. These memory cards were delivered within half a day to clothing distributors in Pyongsong, South Pyongan Province, via "service cars" operated by passenger transport operators.

The distributor would select several outfits from the film that people might like and pass them to an in-house fashion designer. The clothing designs were immediately sent to garment processors, where contract workers began production according to the patterns. These workers were employees of state enterprises who had gained free time by paying part of their earnings to their workplaces.

The finished clothes were loaded into containers operated by logistics transporters called "chapanjangsa" and sent to wholesalers in Sinuiju. There, these garments were rebranded as "South Korean clothes imported via China" and shipped to major cities nationwide—Chongjin, Hamhung, Wonsan, and Haeju.

Meanwhile, the movie on the memory card was passed to content distributors, copied onto thousands of memory devices, and supplied to merchants who wandered near markets throughout the country, whispering "good movies available."

By the time a Korean Wave-obsessed young person secretly watched a "good movie" recommended by their regular vendor, the outfits from the film would appear in markets labeled as "Song Hye-kyo coats" and "Lee Byung-hun jackets," stimulating the purchasing desires of fashion-conscious youth.

This was possible because markets controlled trade and distribution, with donju—smugglers, transporters, processors, and distributors—playing active roles within this system.

◆ Prelude to Collapse

The first signs of the donju's decline became apparent in April 2019.

A trader who had traveled from Pyongyang to China for business told ASIAPRESS in an interview that Pyongyang was in the grip of a major recession:

"Business is so bad that even markets in central areas like Jung District and Moranbong District have noticeable vacant stalls. You can't imagine how many wealthy people have gone bankrupt and collapsed. Many trading companies and coal export companies have gone under."

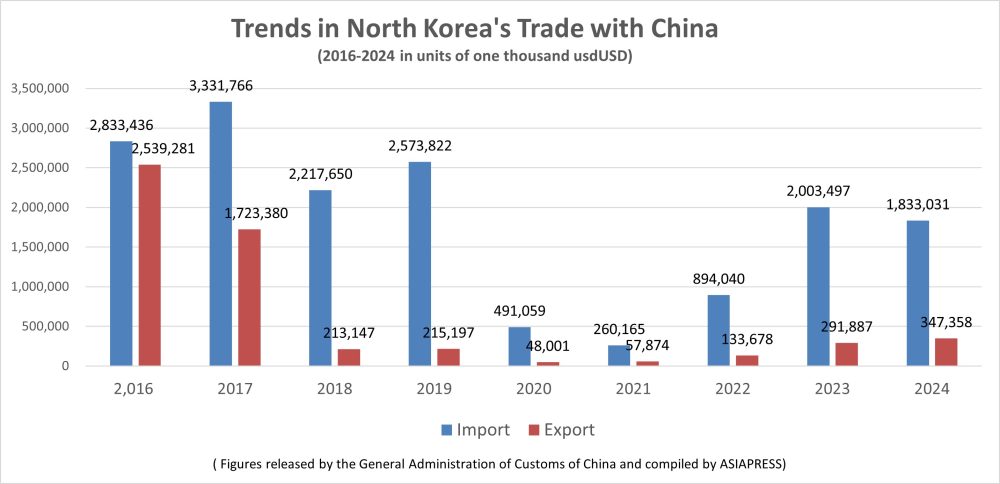

The powerful UN sanctions imposed after North Korea's 2017 nuclear test dealt a direct blow to North Korea's exports. China-bound exports, which comprised the overwhelming majority of North Korea's foreign trade, plummeted from approximately $1.723 billion in 2017 to about $213 million in 2018—a nine-fold decrease.

The sanctions devastated trade, dealing a severe blow to donju involved in trade and distribution. However, this was only the beginning.

The next installment will examine how successive disasters thoroughly destroyed the donju class. (To 2 >>)

※ ASIAPRESS communicates with its reporting partners through Chinese cell phones smuggled into North Korea.

<Special Series>The Rise and Fall of North Korea's Nouveau Riche 'Donju' in the Kim Jong-un Era (2) COVID and Anti-Market Policies... "70-80% of Donju Have Likely Collapsed"

- <North Korea Analysis>How Should We View Kim Jong-un's Agricultural Policy Reform?

- <North Korea Special>What is the Reality of Kim Jong-un's Agricultural Policy Reform? (1) "Collective" Disappears from Farms Major Revisions to Agricultural Regulations

- North-China Border 1,000km Journey by a North Korean Defector and Fourth-Generation Korean-Japanese (1): To the Closest Point to My Ancestral Land, North Korea

- <Video> Call with a N. Korean Woman (1) Expectations for Dialogue with the Lee Jae-myung Administration? "I don't think the Kim regime will do anything with the South..."

![Mass Starvations Occurring in the Breadbasket [pdf]](https://www.asiapress.org/rimjin-gang/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/2012-2013_Hwanghae_Report_A-150x150.jpg)