What kind of lives are our North Korean brothers and sisters living now? Might I catch a glimpse of someone I know? With these thoughts in his heart, journalist JEON Sung-jun headed to the North Korea-China border, ten years after his defection. Standing on land where he could see his hometown from the upper reaches of the Yalu River, gazing at the blue waters, what feelings passed through JEON Sung-jun’s heart?

◆ Standing at the Border Again

This is Changbai County in China's Jilin Province, along the upper reaches of the Yalu River. Across the water lies Hyesan, North Korea. In October 2014, I was a 25-year-old standing on the North Korean mountainside, gazing at the brilliant lights of China, my heart burning with longing for freedom. That night, with six others whose bloodshot eyes nervously scanned our surroundings like rabbits, I crossed the river under cover of darkness.

The late autumn Yalu River at the foot of Mount Baekdu is bone-chillingly cold. But I didn't feel it. While wringing out my wet clothes stiffening from the cold, someone whispered, asking if I was cold, saying I was trembling. I denied it, but if I was indeed trembling, it was more from fear of the border guards at the checkpoint behind us than from the cold. I repeated the promise I had made to my mother, looking toward the North Korean sky:

"I will survive and return."

And now, I stand on Chinese soil in Changbai, the same place I gazed upon with hopeful excitement ten years ago, looking back at my homeland with a heavy heart—a place where I still survive, but can never return to.

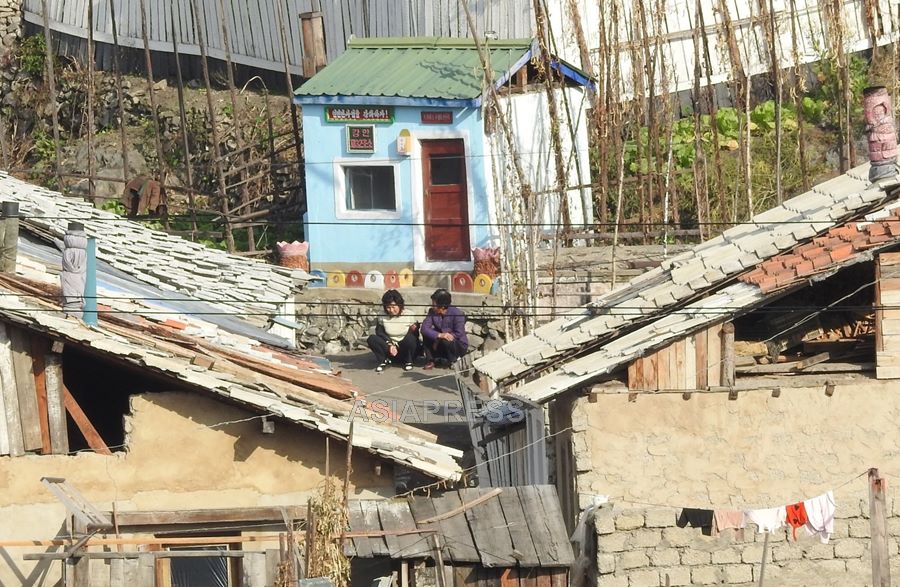

◆ People Trapped Inside

Despite my excitement about finally visiting the North Korea-China border after putting it off for ten years, I couldn't shake a sense of tension. China repatriates North Korean defectors, and North Korean security agents operate covertly in border regions. Throughout our reporting trip, we struggled to avoid surveillance by Chinese polices and their cameras.

When we arrived in Dandong at the lower Yalu River, where North Korea's Sinuiju is visible, I was surprised by my own indifference. Neither the tourists gathered from across China to view North Korea, nor the apartments hastily built in just two months for flood victims after this summer's disaster, stirred much emotion in me. I briefly wondered if something was wrong with my heart. The only thing that moved me was the Yalu River itself—ironically a muddy yellow instead of the blue-green hue that supposedly inspired its name.

We traveled upstream along the Yalu River, observing North Korean cities like Uiju, Manpo, and Jasong. Despite the lingering damage from last summer's floods, the first things restored were the border fences that had been washed away. North Koreans are now completely trapped behind fences and cameras sealing the border. Ten years ago, over a thousand defectors entered South Korea annually; recently, that number has dwindled to dozens or at most a hundred or so. Most of these had escaped long ago and were living in third countries—very few have fled North Korea since the COVID pandemic. Defection has become nearly impossible.