The era in which people can defect from North Korea has almost ended.

That’s the strong feeling I’ve had as I have watched the situation over the past several years. It is not just the impact of COVID-19. While I will explain more about this later in the article, the defector era is in its twilight because the Kim Jong-un regime has ordered his authorities to implement a “zero defector” policy. This policy has led to an unprecedented level of security along the country’s border with China.

The highpoint in the number of defectors entering South Korea was 2,914 in 2009. While defections fell dramatically since Kim Jong-un gained power in 2012, there were at least 1,000 people who made it to South Korea up until 2019. Then, in 2020, the number of defections fell to 229, before falling further to just two percent of that 2009 highpoint to 63 people in 2021. There were only 11 defectors who entered South Korea from January to March 2022. (All of the previous figures are from South Korea’s Ministry of Unification, as are those used below). Moreover, most of the defectors who made it to South Korea in the past couple of years are those who had resided for long periods of time in China. There were few cases in which the defectors had come more or less straight from North Korea.

One female reporting partner living in North Korea’s northern region lamented to me in March of this year, “I wish I had just bitten the bullet and escaped to South Korea three years ago. Now it’s impossible.”

◆ Social disorder caused defections in the 1990s

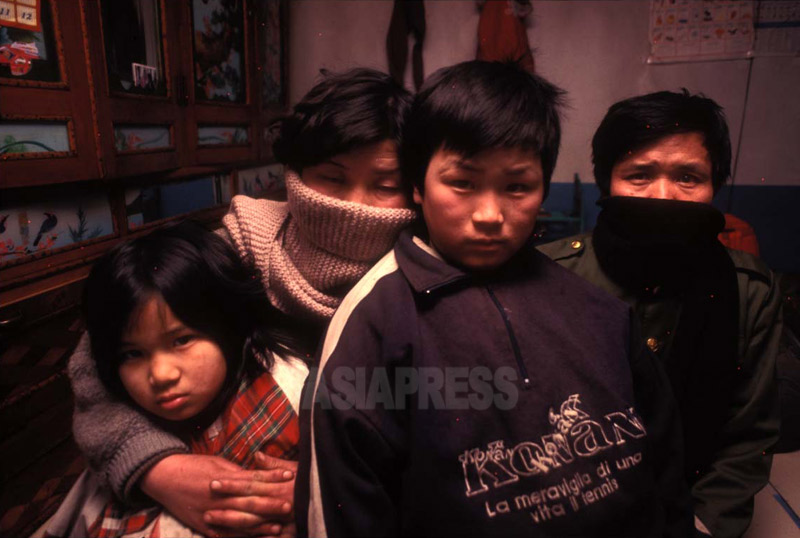

While the dictionary definition of a “defector” from North Korea is a person who “escaped North Korean rule following the Korean War Armistice and settled domestically (South Korea) or abroad,” most defectors actually left North Korea after 1995. In July 1994, as the North Korean economy reached crisis point, Kim Il-sung – the country’s “living god” – died. Kim’s death led to the start of paralysis in the regime’s ability to maintain control, and North Korean society showed signs of crisis. Ultimately, the country’s food distribution system fell apart, leading to a massive famine. While there are different accounts on how many people died, I believe that more than two million people perished by the year 2000. Many people ran away to China to escape hunger and because they could no longer see a future in their country. This was the start of the defector issue, a problem that continues to this day.

I first went on a reporting trip to the China-North Korean border in July 1993. Since then, I have made around 100 such trips to report on conditions in North Korea. My most recent trip to the border region was in September 2019. The flow of people from North Korea to China reached its apex in 1997 to 1998. At the time, I was observing the agricultural villages of Chinese-Koreans along the Tumen and Yalu rivers, and was taken aback by dozens of North Koreans crossing over the border during just one night into a small village of around 1,000 people. I believe that, as of the year 2000, there were probably about one to two million North Koreans who had crossed into China. (There were a lot of people who crossed over multiple times or went back and forth over the border). Most of these people, however, returned to North Korea because they wanted to give their loved ones in North Korea money and food. The minority that abandoned life in North Korea became refugees and settled in China (around 10% of the total people who originally crossed over, I reckon). Ultimately, most of these people sought out a place to settle down for good and made it their goal to reach South Korea.

◆ Defector routes opened by activist groups

The total number of defectors who entered South Korea by 1998 was only 947 people; however, that figure exploded after that, and there are now 33,826 defectors in South Korea as of March 2022. There is a ten-year gap between the highpoint of border crossers into China and the apex of defectors who entered South Korea. The North Koreans who gathered in China were all illegal residents of that country, which meant they had almost no way to make it to South Korea.

In the 2000s, a new defection route that offered protection by the South Korean government was opened by activist groups. This route had defectors walk through the Gobi Desert and into Mongolian territory. This route disappeared after a couple years due to efforts by the Chinese authorities, however. There were then activist groups that took radical steps to facilitate defections: defectors would dash into foreign consulates in Shenyang and Beijing to demand right-of-passage to South Korea. Apart from the so-called “Kim Han-mi Family Incident” of May 2002, when five people dashed into the Japanese consulate in Shenyang, other defectors tried similar attempts at Japanese-run schools.

These defection routes also collapsed after Chinese authorities fortified the areas around foreign consulates. Since that time, the only real route available has been through Southeast Asia. Defectors depart from Kunming in China’s Yunnan Province to make it to Thailand through Laos, Myanmar or Vietnam. This is almost the only available route left for defectors wanting to go to South Korea.

The China-North Korea border in the 1990s was full of holes. People could cross over into China just by handing over a few hundred Chinese yuan as bribes to North Korea’s border patrol. There was also a Chinese-Korean community in China that sympathized with the defectors and protected them. (The defectors migrated to South Korea, Japan, and major cities in China, but this no longer happens).

In particular, North Korean defector women could obtain a safe haven by “getting married” to Chinese-Korean men living in agricultural villages. There was, in essence, a place for North Korean defectors to hide.

However, North Korean authorities believed that the massive number of border crossers was a major crisis, and intensified controls on movement in the country and security along the border with China. China also strengthened its border security following cases of robbery, murders, smuggling of illicit drugs, and human smuggling perpetrated by the border crossers from North Korea. Starting in 2005, there was a noticeable fall in the number of border crossers.