Rising discontent among Pyongyang’s privileged class

Profits from trade with China go directly to the regime’s treasury and are distributed amongst the Pyongyang elite. When trade is brought to a halt, this privileged class feels the pressure, as the exploitative system it relies upon to sustain itself collapses.

Thanks to a Chinese reporting partner for ASIAPRESS, we were able to hear about the situation firsthand from a Pyongyang elite, a senior executive for a state trading company. Meeting the executive in China, the reporting partner asked, “What do you suppose will happen next?”

The executive answered briefly, “It goes without saying that trade right now is difficult. It is very hard now for the high-ranking officials in Pyongyang. Though life is tough, local people can make ends meet by doing menial day jobs. The higher-ups, on the other hand, have lost their only source of income. If this continues, it could become a big problem. There is a lot of discontent."

The executive didn’t elaborate on what he meant by ‘big problem’. As a North Korean with permission to conduct business abroad, there is a lot of trust placed in him by the regime. His lifestyle is only guaranteed if he remains loyal to Kim Jong-un. But if, as the man says, discontent is on the rise, does it mean that Pyongyang’s loyal elite will lose their faith?

The sanctions are not just keeping money out of the hands of North Korean citizens though. The regime too is feeling the pressure and is struggling to maintain its various programs and policies. Although it may present only a small part of the greater picture, we can clearly see evidence of this by studying the North Korean government’s failing national programs, listed below:

▪ Distribution of new national ID cards, which began in late 2017, took until February 2019 to complete.

▪ The tradition of distributing special rations to celebrate holidays and the birthdays of its leaders has been discontinued since the anniversary of Kim Il-sung’s birthday in April of last year.

▪ Construction of the Samjiyeon Special Tourist Zone at the foot of Mt. Baekdu, labeled by Kim Jong-un as a top priority national project, has been delayed due to financial difficulties. Due to sanctions, the project ran out of rebar and other necessary materials.

▪ Due to financial difficulties and soaring fuel prices, military units have been forced to use ox-drawn carts or charcoal-fueled vehicles to transport supplies.

▪ From November last year, the electricity supply for residents across vast northern regions has been cut off almost entirely.

Predicted inflation does not occur...but people’s suffering is on the rise

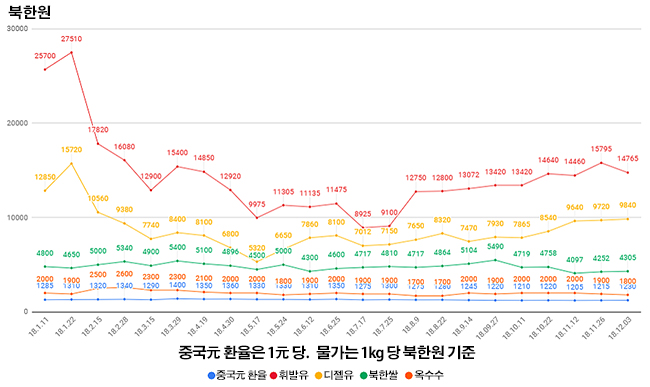

When sanctions were strengthened at the end of 2017, it was anticipated that the North Korean economy would experience heavy inflation. Specifically, the value of the North Korean won was expected to lose its value due to the lack of foreign currency imports. Experts believed that the country’s economy, like that of Zimbabwe and Venezuela before it, could be plunged into chaos due to hyperinflation.

This was not to be, however. Apart from fluctuations in the prices of gasoline and diesel oil, the value of North Korea’s currency remained relatively stable, with only a 20-30 percent increase in the price of food and other commodities reported.

This does not mean to say, though, that North Koreans are living comfortably or that the North Korean economy is doing well. Since November of last year, electricity has been reliably supplied to very few cities outside of Pyongyang. Residents outside of the capital no longer refer to the problem as a ‘power outage’; with no power being provided at all, they say their cities have been ‘powered down’. In addition to the lack of electricity, residents have to deal with demands from authorities for cash and other resources.

The North Korean government frequently extorts resources and cash from citizens in order to complete road repairs, school maintenance, military upgrades, and various other construction projects. Now, with sanctions tightening, the regime has begun to demand even more from the local population.

A reporting partner explained the increasing burden, “The state extorts about 100 Chinese yuan (16,000 South Korean won) from us each month.” This total represents 30-50 percent of an average household’s monthly income.

In addition, starting from December of last year, authorities began forcing all households to enroll in a state-run insurance program. A reporting partner in Yanggang Province said, "We are told to enroll in the insurance program as a show of patriotism. We are not told any information about the contents of the insurance plan or its supposed benefits. We know the state has no money, so it has to take it from us citizens.”

Despite the recent hardship, the reporting partner maintains a strong sense of perspective, saying, "It's hard to earn a lot of money, but there's been no word of people starving to death anywhere. All of us common people have taken to the markets and found a way to make ends meet somehow. These days, there are not people dying in North Korea of starvation like there was before.”

- "You must start with denuclearization"...S. Korean Media Reports that Xi Pressured Kim to Give up Nukes at January Meeting

- <Kim-Trump Summit> Left in the Dark: With No End to Sanctions in Sight, Citizens Face a Long Wait for Electricity

- <Breaking News Interview> "So the sanctions will continue?" North Koreans Face Disappointment as US Summit Breaks Down